Brookings panel explores PROMESA’s implications

David Wessel, director of the Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy, moderates a discussion at Brookings with Puerto Rico Gov. Alejandro García-Padilla.

WASHINGTON — A four-member panel convened here Tuesday to discuss the long-term lessons of Puerto Rico’s debt crisis for other jurisdictions in financial trouble.

“States and municipalities across the U.S. are dealing with some of the same issues Puerto Rico is facing: the need to maintain essential services for their citizens, along with shrinking budgets; the need to fund public pensions, to secure a competitive education for all students, to fight crime and drug trafficking, and to bring security to neighborhoods,” Puerto Rico Gov. Alejandro García-Padilla said in his speech at the Brookings Institution.

“In facing this issue, states have become individual laboratories,” he said. “We need to learn from each other what works, what does not, and why — about errors and achievements, and how to reduce the former and replicate the latter. We have been forced to try tools that have not been tried before. We have had to knock on doors that others might need to approach in the not-too-distant future.”

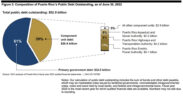

Panelists agreed that jump-starting economic growth and bringing investment back to Puerto Rico is essential in helping the island climb out of its fiscal hole. On June 30, President Obama signed into law the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA) following its passage by both houses of Congress.

Gerald E. Rosen, a former U.S. District Court judge in Michigan and architect of the “grand bargain” that brought Detroit back from the edge of financial ruin, stressed the “need for a robust restructuring under court supervision” — which in Puerto Rico’s case will be done by a financial control board mandated by PROMESA.

“In Detroit, we had an emergency manager,” said Rosen, who is writing a book about those tumultuous times. “Detroit was insolvent. It really wasn’t a city at all. We had to provide a pathway out of bankruptcy so that the city could be a city again.”

Municipal bankruptcy expert James Spiotto, who helped advise Detroit in its Chapter 9 proceedings, said jurisdictions in crisis must not neglect their infrastructure.

“It’s important for municipalities coming into bankruptcy to look at what the city will look like on the other side, and not simply think about restructuring debt,” he said.

Spiotto also said creditors should work with the commonwealth government to ensure that everyone comes out ahead, even though a haircut may be inevitable.

“The market can’t understand unwillingness to pay. But the market historically has understood an inability to pay,” he explained. “You may be a creditor with all the rights to everything, but if you don’t help the municipality to help itself, you’re not going to get paid.”

Yet Natalie Cohen, head of municipal research at Wells Fargo Securities, said it’s clear that investors are worried — and that some of them have been scorned in the media.

“Not everyone investing in Puerto Rico is a vulture or a hedge fund,” she noted. “The value of that investment or who has made it is becoming more prevalent. Certain investors are being punished. In Chapter 11, that’s not an issue. But the law itself should be indifferent as to where the money came from,” she said.

Cohen dismissed suggestions that the financial oversight board required by PROMESA is an “abuse of democracy,” as some have suggested.

“Anytime there’s an oversight body, there’s an outcry that this is an abuse of democracy. I remember the Rev. Malik Shabazz saying he’d rather burn down the city of Detroit than have the state come in. But some oversight programs are, like in North Carolina, not just a monitoring process but pro-active engagement with local government. And people in North Carolina aren’t crying that democracy is being stepped on.”

In Puerto Rico, though, Cohen conceded, “it’s more intense because the political parties are defined by status. Anyone growing up there is aware of the inferiority of services that come from the federal government. That is part and parcel of their identity — even more so than in Detroit.”