Fed report: Irma and Maria had modest, short-term impact on local banks’ performance

Financial losses incurred by banks in Puerto Rico were relatively minor and transitory in the aftermath of hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017, according to a new report by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

The Fed compared Puerto Rico-based banks to a mainland U.S. control group to assess how extreme weather disasters affect bank stability and their ability to lend. The study found that the effects of higher loan delinquency rates on the island were modest and short-lived, with no significant impact on banks’ capital, income or loan growth.

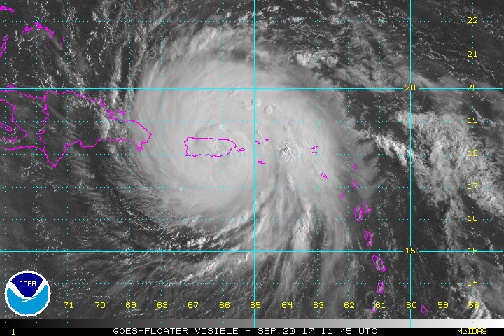

“Puerto Rico was extremely vulnerable even before Maria struck,” the Fed noted. “Its economy and banking sector had contracted for nearly a decade and its water and electrical infrastructure was fragile due to chronic fiscal constraints on investment and maintenance. Compounding matters, Hurricane Irma dropped a foot of rain in Puerto Rico just two weeks before Maria, leaving the island waterlogged and prone to mudslides.”

Given those challenging initial conditions, the report added, Hurricane Maria might represent a worst-case scenario for studying bank resilience against extreme weather.

The study focused on four areas: climate and severe weather, economic conditions and financial environment before the hurricanes, banks’ financial performance around the time the storms hit, and risk mitigants leading to minor impacts to the local banks.

Climate issues

Climate warming has broad scientific consensus, and climate financial risk – climate change’s impact on financial institutions, financial markets and the financial economy – is an active area of study from policy, academic and industry perspectives, the report stated.

Many contractual and market mechanisms exist for banks to protect their financial interests. However, severe climate events may occur that are far beyond the worst outcomes that banks plan for or protect against, so it is an empirical matter whether banks are able to implement sufficient safeguards to protect themselves against unexpectedly severe climate-related events, the Fed reported.According to the Germanwatch Global Climate Risk Index 2021, Puerto Rico ranked highest among 180 countries or territories based on the number of severe weather events, fatalities and economic losses from 2000 to 2019, most of which were related to hurricanes. The island is squarely in “Hurricane Alley,” a swath of the North Atlantic where hurricanes are frequent.

Weather-related disaster declarations have been a yearly occurrence in Puerto Rico since 2001, involving events related to floods, droughts, tropical storms and winter swells, according to the Fed’s report. Of the 45 disasters declared by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) in Puerto Rico since 1955, 28 (62%) have been severe storms and hurricanes.

FEMA recently updated its flood zone maps, indicating which areas are considered at risk of a flood every 100 or 500 years (1% and 0.2% risk zones, respectively). According to a CUNY Hunter study, in 2019 about 15% (488,560) of Puerto Rico’s population resided in the 100-year floodplain, and 19% (624,414) of the population lived in a combined 100- and 500-year floodplain.

In the years leading up to hurricanes Irma and Maria, Puerto Rico’s power and water infrastructure, which was already dilapidated and fragile before the fiscal crisis, deteriorated further because of budget cuts and lack of maintenance. When Maria struck, Puerto Rico experienced the most extensive blackout in U.S. history in terms of magnitude and duration, according to the Fed report.

The destruction and disruption from Maria were unprecedented. Nearly 80% of the island’s electrical grid was destroyed, and most of the island’s 3.4 million residents lost power for months. Thousands of homes were damaged or destroyed, and flash floods caused an estimated 70,000 landslides and destroyed many bridges. FEMA estimated damages from Maria at $90 billion, making it the third costliest hurricane in U.S. history.

The combined damage from Maria and Irma nearly exceeded the island’s entire annual gross domestic product of around $104 billion in 2016, the Fed reported. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that while global public adaptation costs to climate change will grow to 0.25% of global GDP in the coming decades, for small island nations exposed to tropical cyclones and rising seas, that number could reach 20% of GDP.

Before hurricanes Irma and Maria

Before the Great Recession hit the U.S. economy in 2008, an economic downturn was already well underway in Puerto Rico. From 2006 to 2017, Puerto Rico’s population fell by 11%, GDP fell by 10%, and employment fell by 17%, the Fed reported.

As a result of this out-migration and protracted decline in its tax base, exacerbated by a lack of transparency in budgeting, Puerto Rico developed a full-blown fiscal crisis, which did not become widely apparent until 2014.

The local banking industry contracted, along with its economy in the decade before the hurricanes. Bank failures, consolidation and firm exit shrank total assets held by commercial banks operating in Puerto Rico by more than 40% between 2006 and 2016. Total loans outstanding by banks operating on the island also contracted steadily in the years leading up to the storms, according to the report.

Total wage and salary income dropped by about $250 million in the third and four quarters of 2017 but resumed growing by the first quarter of 2018, the Fed reported, noting that growth later in 2018 was more robust than before the hurricanes.

One structural challenge in Puerto Rico is its high poverty rate, higher than in any of the 50 states and roughly twice the national average. Median household income on the island is $21,000, which is about one-third of the mainland level. One contributing factor is a historically low labor force participation rate: less than half of Puerto Rico’s adult population is either working or looking for work, with some of the “missing workers” probably employed in the island’s informal economy, according to the Fed’s report.

Another relevant structural factor relates to homeownership. While homeownership rates in Puerto Rico are comparable to the U.S. mainland, mortgage financing is much less common, with only 41% owner occupied homes being mortgaged versus 67% on the mainland, the Fed reported. Residents in the large “unofficial” housing sector, which includes homes built on public land and subdivided family plots, may lack official title to their property, making a mortgage hard to obtain. This lack of title can also limit homeowners’ access to any FEMA assistance that requires proof of ownership.

After the hurricanes

After the hurricanes

The two hurricanes, occurring two weeks apart, exacerbated the already weak economic and financial conditions in Puerto Rico. After Irma devastated some Caribbean islands, neighbors such as Puerto Rico sent people, aid and supplies, not knowing that a storm of Maria’s magnitude would arrive so shortly afterward. This movement of critical resources away from Puerto Rico hindered the response to Maria, the Fed explained.

Widespread outages of power, water and communication systems, as well as critical damage to roads, bridges and other transportation links, crippled Puerto Rico’s economy in the fall of 2017. From August to October 2017, private-sector employment fell by 7%, but it rebounded fairly quickly, the Fed reported. By December 2017, nearly two-thirds of the initial job loss had been reversed, and by the following summer, employment was back up to pre-storm levels, according to the report.

Bank performance after the hurricanes

The Fed investigated how Puerto Rico banks fared after Irma and Maria struck the island compared to a control group of stateside banks that were not exposed to any natural disaster from the third quarter (Q3) of 2017 to Q3 2019. The study focused on the three banks based in Puerto Rico at the time: Banco Popular de Puerto Rico, FirstBank and Oriental Bank, which according to the Fed, controlled more than 75% of deposits on the island in 2017.

“We find that delinquencies at these banks rose afterwards, but the effects were transitory. Charge-offs, capital, income and lending were not affected while bank default risk fell slightly,” the Fed said, pointing out that the relatively modest, transitory impact of the hurricanes on the banks was consistent with other recent studies.

In terms of residential mortgages, the Fed found that at the time Maria struck, more than 10% of the active mortgages in Puerto Rico were already delinquent. Although the rate roughly tripled by November 2017, it had returned to pre-Maria levels one year later.

Risk mitigants

Given the destruction and disruptions caused by the hurricanes and the weak initial conditions, it is surprising that the impact on banks was not worse, according to the report.

Mortgage holders have several layers of financial protection that can mitigate losses from disaster damages: homeowners’ insurance, flood insurance, federal assistance, and homeowners’ equity. In Puerto Rico homeowner insurance coverage is relatively low, reflecting the low average income and the high cost of insurance in an area where floods and other weather disasters are endemic, the Fed reported.

Homeowners’ and flood insurance

According to research cited by the Fed, only 20% of a sample of 265,807 owner-occupied homes that experienced damage from the 2017 hurricanes had homeowners’ insurance, and that coverage was inversely related to the level of damage from the storms. Of homes that suffered roof damage, only 11% had homeowners’ insurance and less than 4% had flood coverage.

Many residents were unaware of the extent of their coverage, with many filing insurance claims for damage that was covered by their insurance policies. In addition, many had purchased policies from small, private insurance companies that were underregulated and underfunded, some of which failed after the hurricanes without fulfilling their obligations.

U.S. banking laws require flood insurance on homes located in the 1% annual risk floodplain (the 100-year floodplain) with a mortgage issued from a federally backed lender. But there are no requirements for purchase of insurance outside of the 1% annual risk floodplain or from hazards such as wind or landslides, which contributed to losses after the hurricanes.

FEMA disaster assistance

After natural disasters, FEMA provides aid through its Public Assistance, Individual Assistance and Hazard Mitigation Grants (HMGP) programs. The scarcity of flood insurance in Puerto Rico made its residents heavily reliant on FEMA’s disaster assistance, the Fed noted.

Despite lengthy delays in awarding aid, within nine months after Maria, FEMA had approved $1.2 billion in assistance to 452,386 individual applicants, $19.3 billion in public assistance and $54 million in HMGP, according to the report.

However, because most of the aid went to public agencies rather than residents, it would seem to provide little direct protection to banks, the report stated. Moreover, FEMA individual assistance is intended to make homes safe and habitable, not restore them to pre-storm conditions; thus, the property could still be depreciated relative to any mortgage obligation.

The Fed’s study found that mortgages with PMI suffered smaller losses than mortgages without PMI post-Maria, suggesting that PMI acted as a financial loss mitigant for lending institutions.

Mortgage insurance provided by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and the Veterans Administration (VA) helped protect banks in Puerto Rico from financial losses, with post-hurricane loss rates much lower for FHA and VA loans than for loans with or without PMI, the Fed reported.

Bottom Line

Despite back-to-back hurricanes, Maria being the worst one to hit Puerto Rico since 1928, and the island being vulnerable after a decade of economic decline and a shrinking banking sector, the 2017 hurricanes had only a modest, short-term impact on banks’ performance and no negative effects on their lending, the Fed concluded.